Popping iOS <=14.7 with IOMFB

During the last two weeks of my summer (as of writing, summer 2021), I decided to try and take a crack at iOS 14 kernel exploitation with the IOMobileFramebuffer OOB pointer read (CVE-2021-30807). Unfortunately, a couple days after I moved back into school, I found out that the way I was doing exploitation would not work on A12+ devices. An exploit that only works on hardware from 2017 and before is lame, so I scrapped it and started over.

I remembered that @ntrung03 has a professor sponsoring his xnu-qemu project and wondered if my school had something similar, and turns out it does! After accidentally sending three blank emails to my current sponsor with details about my project (thanks Gmail for putting my messages under the button with three dots…), he gave me permission to register for the independent study class. In this case, “sponsor” doesn’t mean I’m getting paid. Since I am getting four credits for this project like I would for any other class, it proves to the school that this is a legit project.

I highly recommend reading the original blog post here. It does a great job of describing the bug so I don’t feel it’s necessary to re-describe it. In short, IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_displayed_fb_surface would not check a user-provided index into an array of pointers to IOSurface objects, leading to a kernel type confusion.

Initial Reconnaissance

Since we can get the kernel to interpret an arbitrary object as an IOSurface, we need to figure out the code paths this object is sent down. There is only one code path that we will always hit with our type confused IOSurface, aka oob_surface:

IOSurfaceSendRight *__fastcall IOSurfaceSendRight::init_IOSurfaceRoot___IOSurface(

IOSurfaceSendRight *a1,

IOSurfaceRoot *a2,

IOSurface *oob_surface)

{

IOSurfaceSendRight *v6; // x20

IOSurface *surface; // x21

v6 = OSObject::init();

a1->m.surface_root = a2;

surface = a1->m.surface;

a1->m.surface = oob_surface;

if ( oob_surface )

(oob_surface->retain)(oob_surface);

if ( surface )

(surface->release_0)(surface);

IOSurface::clientRetain(oob_surface);

IOSurface::increment_use_count(oob_surface);

return v6;

}

Where IOSurface::clientRetain is:

SInt32 __fastcall IOSurface::clientRetain(IOSurface *surface)

{

return OSIncrementAtomic(&surface->client_retain_count);

}

And IOSurface::increment_use_count is:

void __fastcall IOSurface::increment_use_count(IOSurface *surface)

{

do

{

OSIncrementAtomic((surface->qwordC0 + 0x14LL));

surface = surface->qword3F0;

}

while ( surface );

}

There are two primitives here:

IOSurface::clientRetainincrements whatever is at offset0x354of the objectoob_surfacepoints to. (client_retain_countis at+0x354)IOSurface::increment_use_countgives us an arbitrary 32-bit increment in kernel memory if we control the pointer at offset0xc0ofoob_surface.

My mind immediately went to the arbitrary 32-bit increment. I used that exact same primitive to pop iOS 13.1.2 with the kqworkloop UAF back in 2020, so I knew it was enough to pwn the phone.

But let’s step back for a second: we have a type confusion, but if we type confuse with a “bad” object, we’ll panic inside IOSurfaceSendRight::init, since this code (rightfully) assumes it will only deal with objects related to IOSurface. The first order of business is to determine what has to be true of the object we type confuse with in order to not panic:

oob_surfaceshould point to an IOKit object becauseIOSurfaceSendRight::initinvokes the virtual method at offset0x20on its vtable. As long asoob_surfaceinherits fromOSObject, this callsretain, which is a harmless operation.oob_surface’s size should be at least0x358bytes because the fieldIOSurface::clientRetainincrements is at offset0x354. If the objectoob_surfacepoints to is smaller than that, we risk modifying a freed zone element or hitting an unmapped page.oob_surfacemust have a valid kernel pointer forIOSurface::increment_use_countat offset0xc0. At offset0x3f0, the pointer can be valid orNULL. Now, the objectoob_surfacepoints to should be larger than0x3f8bytes for the same reasons as the previous point.

Except for the “valid kernel pointer at offset 0xc0”, these “requirements” are not set in stone. If you found a small, non-IOKit object that doesn’t panic inside IOSurfaceSendRight::init and brings you closer to kernel read/write, that would work as well. I just like to veer on the edge of caution during exploit dev since the compile-run-panic routine gets old very quickly. We could spray smaller objects, enter IOSurfaceSendRight::init with oob_surface pointing to one of those objects, and use the primitives listed above to cause some smaller corruption in/around that object.

But no matter the size of the object (and whether or not it inherits from OSObject), spraying has its own issues, because iOS 14 significantly hardened the zone allocator by introducing kheaps and sequestering.

kheaps

At a high level, kheaps segregate data, kernel, kext, and temporary allocations by giving them their own kalloc.* zones. The kheaps are called KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS, KHEAP_DEFAULT, KHEAP_KEXT, and KHEAP_TEMP, respectively.

The zone map is actually made up of three different submaps. One submap houses the zones for KHEAP_DEFAULT, KHEAP_KEXT, and KHEAP_TEMP, while another houses the zones for KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS. The third submap isn’t important to us. KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS is meant for allocations whose contents are pure bytes or controlled by userspace. KHEAP_DEFAULT is the kheap that XNU allocates from, while KHEAP_KEXT is the kheap that kernel extensions allocate from. KHEAP_TEMP (which just aliases to KHEAP_DEFAULT) is meant for allocations that are done inside system calls that are freed before returning to EL0. So, on iOS 14 and above, an IOKit object that’s 500 bytes would belong to kext.kalloc.512, while a pipe buffer of the same size would belong to data.kalloc.512. On iOS 13 and below, both those allocations would go into kalloc.512. (On iOS 15, it appears that KHEAP_TEMP has been removed)

Okay, but what about zone garbage collection? On iOS 13 and below, abusing zone garbage collection to move a page from one zone to another was the standard when exploiting use-after-frees. When I was exploiting the socket bug from iOS 12.0 - 12.2 (and iOS 12.4, lol) I sprayed/freed a ton of kalloc.192 ip6_pktopts structures (the object you could UAF) and triggered zone garbage collection to send those pages back to the zone allocator. After a page is sent back, it is ready to be used for any zone, not just the for the zone it originally came from. After spraying a ton of kalloc.512 pipe buffers, the just-freed kalloc.192 pages were “repurposed” for my pipe buffers. If the socket bug were alive on iOS 14, this strategy wouldn’t have worked since pipe buffers are quarantined in the data buffers kheap. The days of spraying fake kernel objects through pipe buffers (or any other data-only means) and hoping to “repurpose” those pages with garbage collection are over.

KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS is isolated, while KHEAP_DEFAULT and KHEAP_KEXT share the same submap. So shouldn’t it be possible to use zone garbage collection to “re-purpose” a page from say, kext.kalloc.192 to default.kalloc.512? Or from kext.kalloc.256 to kext.kalloc.768? If you could, that would defeat the purpose of the separation kheaps provide. On iOS 14, the zones that belong to KHEAP_DEFAULT and KHEAP_KEXT are sequestered. This means the virtual memory that backs a given zone will only ever be used for that zone.

Zone Garbage Collection and Sequestering

To understand how garbage collection was changed to work with sequestering, we need to talk about how a zone manages the pages which belong to it.

All zones have a chunk size. This is how many pages of contiguous virtual memory a zone will carve into smaller elements. This range is referred to as a “chunk”. Zones with a small element size, like *.kalloc.192, have a chunk size of one page. But once we start pushing into zones with larger and larger element sizes, such as *.kalloc.6144, chunk size is upped to 2 pages, which is the max for devices with a 16k page size. For devices with a 4k page size, the max chunk size is 8 pages.

The structure that is associated with each page in a chunk in a zone is struct zone_page_metadata (most comments removed for brevity):

struct zone_page_metadata {

zone_id_t zm_index : 11;

uint16_t zm_inline_bitmap : 1;

uint16_t zm_chunk_len : 4;

#define ZM_CHUNK_LEN_MAX 0x8

#define ZM_SECONDARY_PAGE 0xe

#define ZM_SECONDARY_PCPU_PAGE 0xf

union {

#define ZM_ALLOC_SIZE_LOCK 1u

uint16_t zm_alloc_size; /* first page only */

uint16_t zm_page_index; /* secondary pages only */

};

union {

uint32_t zm_bitmap; /* most zones */

uint32_t zm_bump; /* permanent zones */

};

zone_pva_t zm_page_next;

zone_pva_t zm_page_prev;

};

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

If a zone page metadata structure is associated with the first page in a chunk, zm_chunk_len is the chunk size of the zone that zm_index, an index into XNU’s zone_array, refers to. If the chunk size is more than one page, then for the second page and onward, zm_chunk_len is defined as either ZM_SECONDARY_PAGE or ZM_SECONDARY_PAGE_PCPU_PAGE, and zm_page_index acts as an index into the chunk. Otherwise, zm_alloc_size tells us how many bytes in that chunk are currently allocated. zm_page_next and zm_page_prev work together to form a queue of chunks for zm_index’s zone. If a zone page metadata structure is the head for this queue of chunks, zm_page_prev holds a value encoded by zone_queue_encode. If it’s not the head, both point to the first page of the previous/next chunk, but only when the zone page metadata structure they belong to is associated with the first page in a chunk. Ignore the strange zone_pva_t type for now—there will be more on that later.

All zone structures carry pointers to zone page metadata structures, each of which serve a different purpose. On iOS 13 and below, those pointers were called all_free, intermediate, and all_used. all_free maintains a queue of chunks with only free elements, intermediate maintains a queue of chunks with both free and used elements, and all_used maintains a queue of chunks with only used elements. On iOS 14 and up, they were renamed to empty, partial, and full respectively, but their purposes stayed the same.

You’d think that these queues would be declared as zone page metadata structures, right? They aren’t:

struct zone {

/* ... */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_empty; /* populated, completely empty pages */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_partial;/* populated, partially filled pages */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_full; /* populated, completely full pages */

/* ... */

};

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc_internal.h

zone_pva_t again?

typedef struct zone_packed_virtual_address {

uint32_t packed_address;

} zone_pva_t;

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc_internal.h

…okay. Admittedly, I found this to be rather annoying before I realized how powerful this data type is. A zone packed virtual address is really just Bits[49:14] of a kernel pointer with some special rules:

(zone_pva_t)0represents the zero page (akaNULL).- a

zone_pva_twith its top bit set can be converted back to its corresponding page-aligned kernel pointer by shifting it to the left14bits and sign-extending. - a

zone_pva_twith its top bit cleared represents a queue address.

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc_internal.h

The cool thing about this is you can convert a non-queue zone_pva_t back to its corresponding zone page metadata structure and vice-versa with zone_pva_to_meta and zone_pva_from_meta, respectfully. Not only that, but once we have a pointer to a zone page metadata structure, we can derive the page in the chunk it is associated with by calling zone_meta_to_addr. For example, zone_pva_to_meta(z->z_pageq_empty) would return the zone page metadata structure which represents the head of the empty queue for the zone pointed to by z.

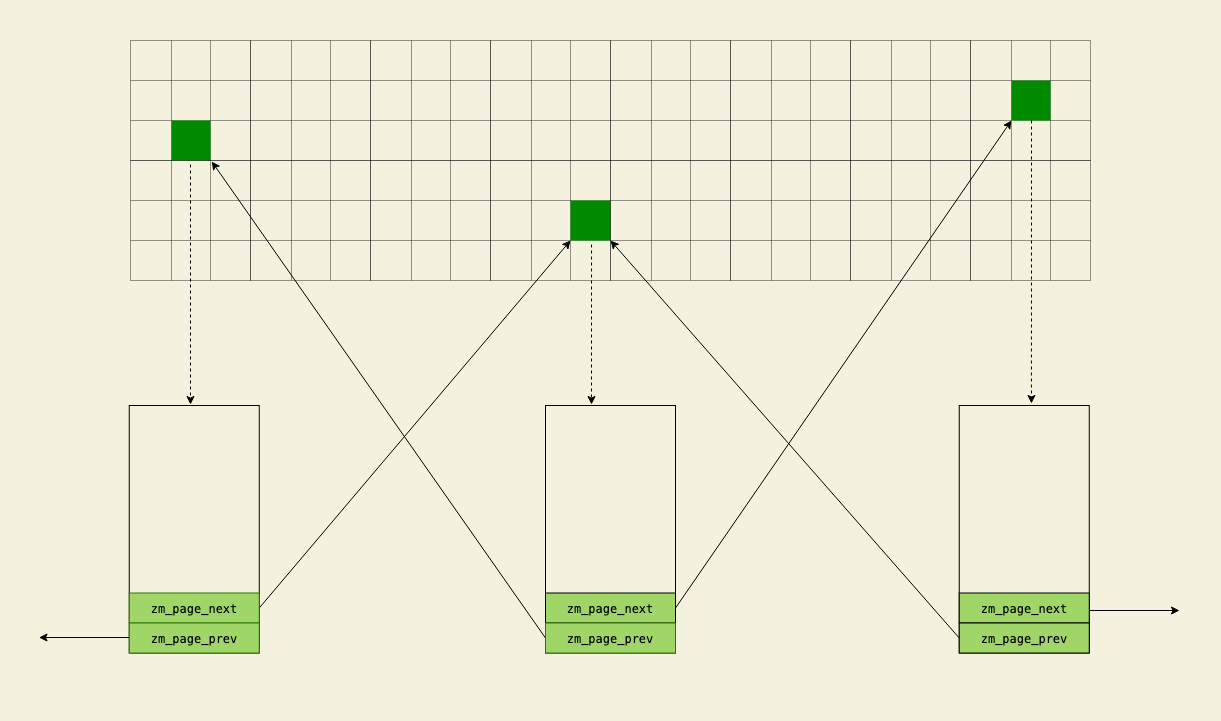

Because that was a lot of words, I made a diagram which attempts to show how everything comes together. Here, all the chunks belonging to some zone are laid out as boxes in a grid, where each box represents one chunk. A dotted arrow stemming from a chunk to a metadata structure indicates association between the two. Assuming that the three dark green chunks have back-to-back zone_page_metadata entries in the middle of one of the queues described earlier, we would have something like this:

I also wrote a program that accepts a size from the command line and dumps the empty, partial, and full queues for the zone that size corresponds to here. After you finish reading this section, if you’re still a bit confused about zones and metadata, I really recommend playing around with that code. Hands-on experience is always better than reading.

Now we can get to garbage collection. zone_gc, the entrypoint to zone garbage collection, calls zone_reclaim_all. zone_reclaim_all is responsible for invoking zone_reclaim on every zone. The interesting bits start at the end of zone_reclaim:

for(;;){

/* ... */

if (zone_pva_is_null(z->z_pageq_empty)) {

break;

}

meta = zone_pva_to_meta(z->z_pageq_empty);

count = (uint32_t)ptoa(meta->zm_chunk_len) / zone_elem_size(z);

if (z->z_elems_free - count < goal) {

break;

}

zone_reclaim_chunk(z, meta, count);

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

The purpose of garbage collection is to release the pages which only have free elements back to the zone allocator. Recall that this is what z_pageq_empty represents. You can see the conversion from zone_pva_t to struct zone_page_metadata * to get the metadata for the current empty (aka all_free) chunk.

This first thing zone_reclaim_chunk does is dequeue the zone page metadata passed to it from z->z_pageq_empty so the above loop from zone_reclaim does not go forever:

static void

zone_reclaim_chunk(zone_t z, struct zone_page_metadata *meta, uint32_t free_count)

{

/* Declaring variables */

zone_meta_queue_pop_native(z, &z->z_pageq_empty, &page_addr);

/* ... */

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

And now we’re at the good stuff: sequestering. At the end of zone_reclaim_chunk, you’ll find this:

if (sequester) {

kernel_memory_depopulate(zone_submap(z), page_addr,

size_to_free, KMA_KOBJECT, VM_KERN_MEMORY_ZONE);

} else {

kmem_free(zone_submap(z), page_addr, ptoa(z->z_chunk_pages));

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

Again, sequester will always be true for KHEAP_DEFAULT and KHEAP_KEXT. While kmem_free releases the chunk and the physical memory backing that chunk, kernel_memory_depopulate only releases the physical memory. So XNU is no longer freeing the contiguous virtual memory that makes up a chunk for sequestered zones during garbage collection? A memory leak like that is unacceptable, so what’s the deal? If we scroll down a couple of lines, we’ll see this:

if (sequester) {

zone_meta_queue_push(z, &z->z_pageq_va, meta);

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

Oh, okay, so the zone page metadata for the just-depopulated chunk is pushed onto a queue called z_pageq_va. First introduced in iOS 14, it sits right after z_pageq_full in struct zone:

struct zone {

/* ... */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_empty; /* populated, completely empty pages */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_partial;/* populated, partially filled pages */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_full; /* populated, completely full pages */

zone_pva_t z_pageq_va; /* non-populated VA pages */

/* ... */

};

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc_internal.h

Alright, so how is XNU using z_pageq_va? The answer is in zone_expand_locked. If a zone starts to run out of free elements, this function may be called to refill that zone. One of the first things it does is see if it can reuse a depopulated chunk from z_pageq_va:

if (!zone_pva_is_null(z->z_pageq_va)) {

meta = zone_meta_queue_pop_native(z,

&z->z_pageq_va, &addr);

if (meta->zm_chunk_len == ZM_SECONDARY_PAGE) {

cur_pages = meta->zm_page_index;

meta -= cur_pages;

addr -= ptoa(cur_pages);

zone_meta_lock_in_partial(z, meta, cur_pages);

}

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

Wait, why is this code checking if addr is not the first page in the chunk? I didn’t mention this earlier because I had not yet explained the purpose of z_pageq_va, but a chunk can actually be comprised of populated and depopulated virtual memory. This is a big deal because it can be difficult to allocate enough pages for an entire chunk when the system is stressed for free memory. Partially-populated chunks benefit 4K devices more than 16K devices, since again, the maximum chunk size for 4K is 8 pages, as opposed to 2 pages for 16K. The first page of a partially-populated chunk will always be populated. Whether or not the following pages are populated of course depends on how much free memory there is.

If we shift focus back to zone_expand_locked, we see that XNU tries to grab enough free pages with vm_page_grab to satisfy min_pages, not the chunk size for the zone z. min_pages is the element size for z rounded up to the nearest page. This is what could end up producing a partially-populated chunk later, since nothing here enforces that a free page is to be allocated for every page in the chunk addr belongs to:

while (pages < z->z_chunk_pages - cur_pages) {

vm_page_t m = vm_page_grab();

if (m) {

pages++;

m->vmp_snext = page_list;

page_list = m;

vm_page_zero_fill(m);

continue;

}

if (pages >= min_pages && (vm_pool_low() || waited)) {

break;

}

/* ... */

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

Next, kernel_memory_populate_with_pages is called to remap the depopulated virtual memory from the recently-popped z_pageq_va chunk onto the physical memory backing the free pages which were just allocated. However, if XNU couldn’t allocate enough free pages to satisfy the length of that chunk, some pages in that chunk will remain depopulated after kernel_memory_populate_with_pages returns, producing a partially-populated chunk.

kernel_memory_populate_with_pages(zone_submap(z),

addr + ptoa(cur_pages), ptoa(pages), page_list,

zone_kma_flags(z, flags), VM_KERN_MEMORY_ZONE);

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

Finally, zcram_and_lock is called. This function is responsible for making the remapped chunk once again usable for a zone. If this chunk ended up being partially-populated, it makes sure the depopulated pages make it back to z_pageq_va:

/* ... */

if (pg_end < chunk_pages) {

/* push any non populated residual VA on z_pageq_va */

zone_meta_queue_push(zone, &zone->z_pageq_va, meta + pg_end);

}

/* ... */

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

To sum everything up, the new zone garbage collection/zone expansion flow provides a really strong guarantee: because the virtual memory for sequestered pages is not actually freed to the zone map, it is impossible to re-use that virtual memory for another zone. And if kheaps uphold their promises of separation, spraying is looking less and less viable.

There’s one small thing I did not mention earlier: the zones backing KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS are not sequestered. But this doesn’t matter, since these zones live cold and alone in a different submap than the zones that belong to KHEAP_DEFAULT and KHEAP_KEXT. I also lied about the program that dumps queues earlier—in addition to dumping empty, partial, and full, it’ll also dump va.

It’s also possible for kernel extension developers to choose to back their IOKit objects with a zone specifically for that object instead of sticking them in KHEAP_KEXT. We are truly in the dark ages. Take me back to iOS 13, please :(

kmem_free(zone_map, free_page_address, size_to_free);

xnu-6153.141.1/osfmk/kern/zalloc.c

There is another problem when exploiting this vulnerability: we can interpret a pointer, not arbitrary bytes, as an IOSurface object. We can’t just index into a KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS zone we sprayed earlier to get a send right to an IOSurface object backed by sprayed bytes. If we could, exploitation would be much more trivial. Instead, we have to provide an index that hits some kernel pointer, or else we’ll panic. The array that we can read out-of-bounds from lives inline (IOSurface*[], not IOSurface**, ) on a gigantic, 0x13a0-byte UnifiedPipeline object inside kext.kalloc.6144. kext.kalloc.6144 is relatively quiet, so if we sprayed this zone, we would eventually end up with allocations surrounding this UnifiedPipeline object. But I could not find a way to make kext.kalloc.6144 allocations from the app sandbox. And even if I could, I would be unable to garbage collect a page from a different KHEAP_KEXT zone to place it near the UnifiedPipeline object because of sequestering.

With zone garbage collection nerfed into the ground and no way to shape kext.kalloc.6144, spraying is not looking good. We’d literally be making a blind guess about the distance from a kext.kalloc.6144 page to a sprayed object, and that would have an abysmal success rate.

The Light in the Middle of the Pipeline

Hold on, 0x13a0 bytes for a kernel object? That is excessively large, and opens the door to a lot of potential pointer fields. And again, since the array is defined inline, accesses to it look like *(UnifiedPipeline + 0xa98 + (0x8 * idx)) and not *(*(UnifiedPipeline + 0xa98) + (0x8 * idx)) In case you missed it, 0xa98 is the offset of the IOSurface array we can read out-of-bounds from (at least on my phones). Thus, we’re able to read off any pointer field from the UnifiedPipeline object and type confuse with it. This has got to lead somewhere, so I dumped the fields which resembled a kernel pointer and derived the objects those pointers represented. The format is the following: <offset>: <object class> (<size>).

0x18: OSDictionary (0x40)

0x20: OSDictionary (0x40)

0x30: AppleARMIODevice (0xd8)

0x60: IOServicePM (0x288)

0x7f8: IOSurface (0x400)

0x810: IODMACommand (0x78)

0xb28: IOMFBSwapIORequest (0x640)

0xba8: IODARTMapper (0x690)

0xbb0: IOSurfaceRoot (0x1f0)

0xbb8: IOCommandGate (0x50)

0xbc0: IOWorkLoop (0x48)

0xbc8: IOSurface (0x400)

0xbd0: IOPMServiceInterestNotifier (0x88)

0xbd8: IOInterruptEventSource (0x68)

0xbe0: AppleARMIODevice (0xd8)

0xbe8: IOTimerEventSource (0x60)

0xd30: IOSurfaceDeviceMemoryRegion (0x60)

0xd40: IOCommandPool (0x38)

0xd68: AppleMobileFileIntegrity (0x88)

0x1230: VideoInterfaceMipi (0x78)

0x12d8: AppleARMBacklight (0x358)

While analyzing this list of objects, I was asking myself two questions. The first question was whether or not a given object would fulfill my “requirements” to type confuse with and the second question was if I could create that object from the app sandbox.

I immediately put any objects smaller than IOSurface on the back-burner. I’d come back to those if the larger objects did not work out. There’s an actual IOSurface object at offset 0x7f8… but then I’d just be giving what IOSurfaceSendRight::init expects, so I wouldn’t be able to take advantage of the type confusion primitives. I turned my focus to objects larger than IOSurface: IODARTMapper and IOMFBSwapIORequest. Both of these inherit from OSObject, so the virtual method call IOSurfaceSendRight::init does will be harmless. But if I’m being honest, IODARTMapper does not sound like an object I could create from the app sandbox, so I scrapped it immediately. The only one left is the IOMFBSwapIORequest object at offset 0xb28.

The word “swap” brought back a lot of memories because I had reverse engineered IOMobileFramebufferUserClient’s external methods in early 2020 and remembered a lot of references to swaps. I took another look, and sure enough, there are a bunch of external methods which have “swap” in them:

External method 4: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_start

External method 5: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submit

External method 6: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_wait

External method 20: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_signal

External method 52: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_cancel

External method 69: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_set_color_matrix

External method 81: IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_cancel_all

Can we allocate IOMFBSwapIORequest objects from the app sandbox? Well, IOMobileFramebufferUserClient is openable from the app sandbox, and there’s seven external methods related to swaps, so that provides some of insight to the answer.

When invoking external method 4, IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_start, we’ll eventually land inside IOMobileFramebufferLegacy::swap_start. That function calls IOMFBSwapIORequest::create to allocate a new IOMFBSwapIORequest object. After a bit of initialization, the swap ID for the newly-created swap is figured out, and is passed back to us as the only scalar output of this external method. So, yes, we can create IOMFBSwapIORequests from userspace.

But the bit of initialization that IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_start does to the newly-created IOMFBSwapIORequest is out of our control, so I took a look at external method 5, or IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submit. Even though its external method structure says it takes a variable amount of structure input, it will error out for any size other than 0x280 bytes (at least for 14.6 and 14.7).

0x280 bytes is a good amount of controllable input. Weirdly enough, there’s no scalar input, since the swap ID of the IOMFBSwapIORequest to “submit” is passed via the structure input instead. After invoking IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submit, we’ll eventually end up inside UnifiedPipeline::swap_submit. This is a large function that copies most of our structure input to the IOMFBSwapIORequest object that corresponds to the swap ID we specified. The parts of the structure input that are not copied directly to the object are things like IOSurface IDs. Those IDs are instead used to derive IOSurface pointers, and those pointers are written to the object. One interesting thing about this function is it reads a userspace pointer from the structure input, creates an IOBufferMemoryDescriptor object from that pointer and the current task, then copies 0x20c bytes from that memory to the IOMFBSwapIORequest object, starting from offset 0x366. So we really have 0x280 + 0x20c bytes of controlled input. I actually overlooked this for most of the time I was writing the exploit! But since IOMFBSwapIORequest::create zeros out the IOMFBSwapIORequest it allocates, those bytes just remained zero. Looking back, it would not have really made a difference for exploitation.

Let’s come back to the third requirement of the type confusion: will there be a non-NULL pointer at offset 0xc0 and a non-NULL (or NULL) pointer at offset 0x3f0? First, let’s check if we have control over these bytes, since that implies we’ll be able to create these conditions ourselves. The annoying thing is that this function was compiled in such a way that it is hard to quickly eyeball if we have control over offset 0xc0. Nevertheless, we do control those eight bytes:

for ( k = 0; k < *(_DWORD *)(found_swap + 356 + 4LL * j); ++k )

{

v26 = (int *)(input_swap + 268 + ((__int64)j << 6));

v27 = v26[4 * k + 1];

v28 = v26[4 * k + 2];

v29 = v26[4 * k + 3];

v30 = (_DWORD *)(found_swap + 113 + ((__int64)j << 6) + 0x10LL * (int)k);

*v30 = v26[4 * k];

v30[1] = v27;

v30[2] = v28;

v30[3] = v29;

}

found_swap is the IOMFBSwapIORequest we are submitting and input_swap is our structure input. *(_DWORD *)(found_swap + 356 + 4LL * j) is controllable, but was validated to fall in the range [0, 4]. On the contrary, it’s very easy to see we also control the eight bytes at offset 0x3f0, since that is part of the 0x20c-byte region which is copied from the userspace pointer we provide on the structure input:

if ( (*(found_swap + 868) & 1) != 0 && *(input_swap + 56) )

{

*(found_swap + 869) = 1;

v55 = 0LL;

address = *(input_swap + 56);

task = current_task();

v55 = IOMemoryDescriptor::withAddressRange(address, 0x20CuLL, 3u, task);

if ( v55 )

{

if ( (v55->prepare)(v55, 0LL) )

panic("\"%s System error: Failure to prepare memory descriptor\\n\"", "swap_submit");

v54 = -1431655766;

v54 = (v55->readBytes)(v55, 0LL, found_swap + 0x366, 0x20CLL);

if ( v54 != 0x20CLL )

panic("\"%s System error: Mismatched data size\\n\"", "swap_submit");

}

(v55->complete)(v55, 0LL);

(v55->release_0)(v55);

}

}

When I was messing around with input data I tripped these checks a couple times, only to be let down when I checked the panic log.

Cool, so we can control the pointers at offsets 0xc0 and 0x3f0. If we type confuse with this object, then we can do a 32-bit increment anywhere in kernel memory. The only thing left to figure out is if we can get a pointer to an IOMFBSwapIORequest object we submit written to the UnifiedPipeline object. The answer to that lies near the bottom of UnifiedPipeline::swap_submit:

v63 = IOMobileFramebufferLegacy::swap_queue(UnifiedPipeline, found_swap);

After digging through that function, it turns out there is a tail queue of IOMFBSwapIORequest objects starting at offset 0xb18 in the UnifiedPipeline object. Eventually, IOMobileFramebufferLegacy::queue_move_entry_gated is called. Near the middle of it, there is an obvious TAILQ_INSERT_TAIL:

*(found_swap + 0x630) = 0LL;

*(found_swap + 0x638) = UnifiedPipeline_swap_tailq_B18->tqe_last;

*UnifiedPipeline_swap_tailq_B18->tqe_last = found_swap;

UnifiedPipeline_swap_tailq_B18->tqe_last = (found_swap + 0x630);

Since the TAILQ_HEAD macro initializes tqe_last to point to the address of tqe_first, the third line writes found_swap to offset 0xb18 of the UnifiedPipeline object. So every time we successfully invoke IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submit, we can count on a pointer to the swap specified in the structure input to appear at offset 0xb18 of the UnifiedPipeline object.

With everything we know up to this point, we should be able to increment 32 bits of kernel memory with the following steps:

- Create a new

IOMFBSwapIORequestwithIOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_start. - Use

IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submitto get controlled bytes at offsets0xc0and0x3f0of theIOMFBSwapIORequestobject created in step 1.0xc0will be our supplied kernel pointer and0x3f0will beNULL. The pointer to that swap object will be written to offset0xb18of theUnifiedPipelineobject. - Invoke

IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_displayed_fb_surfacewith the out-of-bounds index16, since0xb18 - 0xa98is0x80, and0x80 / sizeof(IOMFBSwapIORequest *)is16. We will enterIOSurfaceSendRight::initwithoob_surfacepointing to theIOMFBSwapIORequestobject, andIOSurface::increment_use_countwill happily increment the 32 bits pointed to by that swap’s eight controlled bytes at offset0xc0.- In case you forgot,

0xa98is the offset of theIOSurfacearray we can read out-of-bounds from.

- In case you forgot,

(Even after all this, I am still not sure what the IOMFBSwapIORequest object at offset 0xb28 of the UnifiedPipeline object is for, since I ignored it after figuring out the strategy above)

Let’s test this theory by placing a nonsense pointer like 0x4141414142424242 at offset 0xc0 of the swap. If the kernel dereferences it inside OSIncrementAtomic, then we are golden:

{"bug_type":"210","timestamp":"2021-11-03 13:06:45.00 -0400","os_version":"iPhone OS 14.6 (18F72)","incident_id":"D6CE2A99-9C2A-49E4-8150-D648AC1F3BE6"}

{

"build" : "iPhone OS 14.6 (18F72)",

"product" : "iPhone10,4",

"kernel" : "Darwin Kernel Version 20.5.0: Sat May 8 02:21:43 PDT 2021; root:xnu-7195.122.1~4\/RELEASE_ARM64_T8015",

"incident" : "D6CE2A99-9C2A-49E4-8150-D648AC1F3BE6",

"crashReporterKey" : "1db1b5662483938458430f8a3af5439dc5f1064d",

"date" : "2021-11-03 13:06:45.03 -0400",

"panicString" : "panic(cpu 2 caller 0xfffffff028aff2d4): Unaligned kernel data abort. at pc 0xfffffff0289b230c, lr 0xfffffff028e5409c (saved state: 0xffffffe8045eb380)

x0: 0x4141414142424256 x1: 0x0000000000000000 x2: 0xfffffff0289b4fac x3: 0x0000000000000000

x4: 0x0000000000000000 x5: 0x0000000000000000 x6: 0x0000000000000000 x7: 0x0000000000000330

x8: 0x0000000000000001 x9: 0x0000000000000001 x10: 0x0000000000000002 x11: 0xffffffe4cc2ca458

x12: 0x0000000000000001 x13: 0x0000000000000002 x14: 0xffffffe19cc1a920 x15: 0x0000000000000003

x16: 0x0000000000000000 x17: 0x000000000000000f x18: 0xfffffff028aed000 x19: 0xffffffe4cc2ca450

x20: 0x0000000000000001 x21: 0x0000000000000000 x22: 0xffffffe4cc1a0860 x23: 0x00000000e00002c2

x24: 0x0000000000000000 x25: 0xffffffe8045ebaec x26: 0xffffffe4cd7601f0 x27: 0xffffffe4cd80ebf4

x28: 0x0000000000000000 fp: 0xffffffe8045eb6e0 lr: 0xfffffff028e5409c sp: 0xffffffe8045eb6d0

pc: 0xfffffff0289b230c cpsr: 0x60400204 esr: 0x96000021 far: 0x4141414142424256

The kernel slide for that boot was 0x209f8000. 0xfffffff0289b230c - 0x209f8000 corresponds to the ldadd w8, w0, [x0] inside OSIncrementAtomic for my iPhone 8. If you’re wondering why x0 is not 0x4141414142424242, IOSurface::increment_use_count adds 0x14 to the pointer it passes to OSIncrementAtomic. That’s not an issue, though. We just need to subtract 0x14 from the pointer we want to use with this arbitrary 32-bit increment. Check out increment32_n from my exploit to see its implementation.

A 32-bit Let Down

After I figured out the arbitrary 32-bit increment, I started thinking about how I could use it. And then I realized something: I need to supply a kernel pointer to do the arbitrary increment, but I don’t have any kernel pointers and I don’t have an info leak. I guess I was so excited after figuring out the 32-bit increment that I never considered this.

I decided to dig a bit further. I knew that every time I did the increment with IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_displayed_fb_surface, it returned a Mach port name via its scalar output. In the kernel, this port is backed by an IOSurfaceSendRight object. IOSurfaceSendRight is a small object that normally carries a pointer to an IOSurface. But for us, this will be a pointer to an IOMFBSwapIORequest object, and for simplicity, I’ll refer to these ports as “swap ports” from now on.

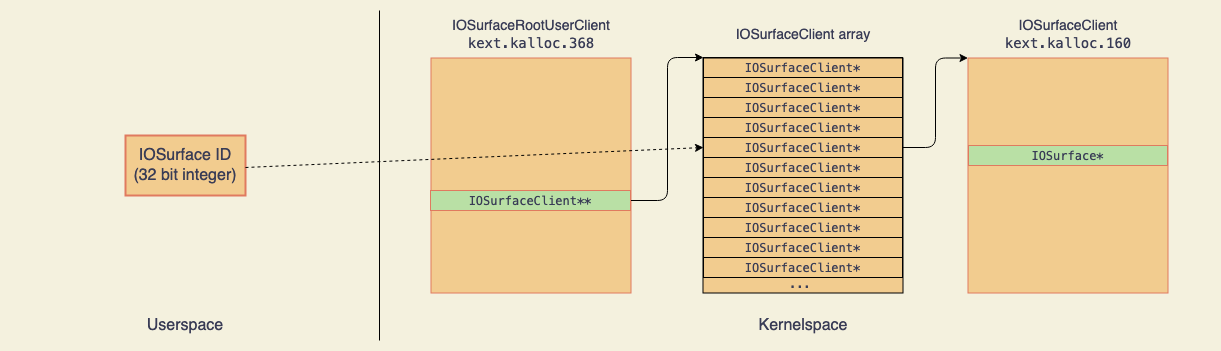

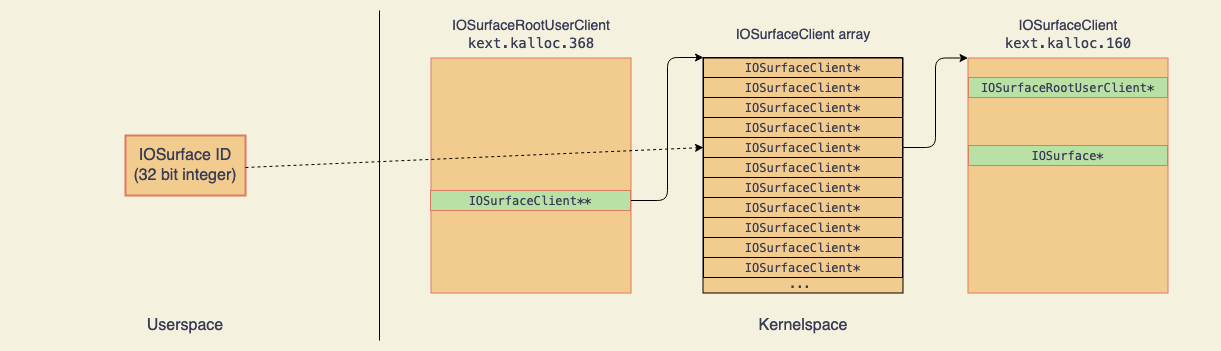

While we are out here dealing with ports, 99% of the IOSurface kext deals with IDs. The bigger picture is this: every IOSurfaceRootUserClient client maintains its own array of IOSurfaceClient objects. An IOSurface ID is really just an index into that array. If the IOSurfaceClient pointer at some index is NULL, that index is considered to be a free IOSurface ID. The IOSurfaceClient object is what carries a pointer to an IOSurface. This can be summed up with one line of code:

IOSurface *surface = IOSurfaceRootUserClient->surface_client_array[surface_id]->surface;

Or with the following diagram:

The green boxes represent structure fields. The array of IOSurfaceClient pointers for an IOSurfaceRootUserClient is at offset 0x118 and the IOSurface pointer for an IOSurfaceClient object is at offset 0x40.

For 99% of this kext, if there is no IOSurfaceClient object for some IOSurface ID, the IOSurface object corresponding to that ID may as well not exist. And this is exactly our issue—all we have is a port. Fortunately, IOSurfaceRootUserClient’s external method 34, IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_lookup_surface_from_port, aims to solve this issue. It takes in a Mach port backed by an IOSurfaceSendRight object and spits out a surface ID, along with many other bytes that I have no idea the purpose of.

My first thought was to use IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_lookup_surface_from_port to get an ID for one of the swap ports. Then I’d use that ID in combination with other IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods to try and leak the IOSurface pointers that were written to the swap object inside IOMobileFramebufferUserClient::s_swap_submit.

When invoking IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_lookup_surface_from_port with a swap port, it will realize that no IOSurfaceClient object exists for the IOMFBSwapIORequest that’s attached to the backing IOSurfaceSendRight object. As a result, a new IOSurfaceClient object will be allocated and IOSurfaceClient::init will be called. The unimportant parts have been snipped:

__int64 __fastcall IOSurfaceClient::init_IOSurfaceRootUserClient___IOSurface___bool(

IOSurfaceClient *a1,

IOSurfaceRootUserClient *iosruc,

IOSurface *oob_surface,

char a4)

{

/* ... */

a1->m.surface = oob_surface;

/* ... */

a1->m.surface_id = 0;

a1->m.user_client = iosruc;

/* ... */

if ( !IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle(iosruc, a1, oob_surface->surface_id) )

return 0LL;

a1->m.surface_id = oob_surface->surface_id;

/* ... */

surface = a1->m.surface;

field_B8 = surface->field_B8;

v13 = field_B8 | (((*(*surface->qword38 + 0xA8LL))(surface->qword38) == 2) << 12) | 0x4000001;

/* ... */

return v16;

}

Just like with IOSurfaceSendRight::init, oob_surface points to an IOMFBSwapIORequest object. The call to IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle does exactly what’s needed to make the new IOSurfaceClient object visible to the IOSurface kext:

__int64 IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle(

IOSurfaceRootUserClient *iosruc,

IOSurfaceClient *iosc,

__int64 wanted_handle)

{

if ( wanted_handle && iosruc->m.surface_client_array_capacity > wanted_handle )

goto LABEL_4;

result = IOSurfaceRootUserClient::alloc_handles(iosruc);

if ( result )

{

LABEL_4:

surface_client_array = iosruc->m.surface_client_array;

if ( surface_client_array[wanted_handle] )

panic(

"\"IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle asked to set handle %08x that was not free: %p\"",

wanted_handle,

iosruc->m.surface_client_array[wanted_handle]);

surface_client_array[wanted_handle] = iosc;

return 1LL;

}

return result;

}

If this function succeeds, an IOSurfaceClient object with a pointer to an IOMFBSwapIORequest will be registered inside the IOSurfaceClient array of the IOSurfaceRootUserClient object which was used to invoke IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_lookup_surface_from_port. There’s one last question: what is the value of the wanted_handle parameter? Since it comes from oob_surface->surface_id, let’s check the offset of surface_id (x20 is oob_surface):

LDR W2, [X20,#0xC] ; a3

MOV X0, X21 ; a1

MOV X1, X19 ; iosruc

BL IOSurfaceRootUserClient__set_surface_handle

So the surface ID for an IOSurface is the 32 bits at offset 0xc. Can we control the 32 bits at offset 0xc on an IOMFBSwapIORequest object? I’ll save you the pain and offer you the answer: no, we can’t control it, and it remains zeroed because IOMFBSwapIORequest::create zeroes out new IOMFBSwapIORequest objects. Okay, so what if it’s zero? Isn’t that still a valid ID? The answer to that is again, no, since IOSurface IDs start at one. Zero is considered to be an invalid ID. If anyone reading this figured out how to control the 32 bits at offset 0xc on an IOMFBSwapIORequest I’d love to hear it, since I spent hours and hours trying to figure that out to no avail.

There’s also another issue with IOSurfaceClient::init, which is the virtual method call near the bottom:

a1->m.surface = oob_surface;

/* ... */

surface = a1->m.surface;

field_B8 = surface->field_B8;

/* ... */

v13 = field_B8 | (((*(*surface->qword38 + 0xA8LL))(surface->qword38) == 2) << 12) | 0x4000001;

This call is unavoidable if we want IOSurfaceClient::init to return a success code. Although we do control the eight bytes at offset 0x38 (which is what qword38 represents), we have no way of forging PACs for vtable pointers, and an exploit that only works on A11 and below is, and always will be, lame.

It looks like taking advantage of IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_lookup_surface_from_port to get an IOSurface ID for a swap port is going to be a no-go. This was a really big let down because I was looking forward to seeing what kind of primitives would introduce themselves by type confusing inside of other IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods.

A Dangerous Guessing Game

With no info leak and another dead end, I was starting to get desperate for anything that would help me start exploitation. Then I remembered something: when Brandon Azad was writing oob_timestamp, he deliberately chose to profile his device to guess the page of kernel memory where his fake tfp0 port would live. I wonder if I could do the same sort of thing…

Of course, with tfp0 long dead, we wouldn’t be creating a fake tfp0. But knowing the address of some buffer in kernel memory would be a solid start to exploitation. But isn’t the zone map a thing of nightmares now? Yes, but the zone map isn’t the only place to make controlled allocations inside the kernel.

There’s something really nice about the kalloc family of functions (or macros, if you want to be completely correct): if the allocation size is far too large to fit into any zone, memory from outside the zone map is returned instead. All kalloc variants call kalloc_ext, which begins by selecting the zone for the allocation size passed in:

struct kalloc_result

kalloc_ext(

kalloc_heap_t kheap,

vm_size_t req_size,

zalloc_flags_t flags,

vm_allocation_site_t *site)

{

vm_size_t size;

void *addr;

zone_t z;

size = req_size;

z = kalloc_heap_zone_for_size(kheap, size);

if (__improbable(z == ZONE_NULL)) {

return kalloc_large(kheap, req_size, size, flags, site);

}

/* ... */

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/kalloc.c

kalloc_heap_zone_for_size will return ZONE_NULL if the size passed to it is larger than kalloc_max_prerounded. This is the smallest allocation size, before rounding, for which no zone exists. For both iOS 14.6 and iOS 14.7, kalloc_max_prerounded is 32769 bytes, since the largest zone in any kheap is for allocations of up to 32768 bytes. Thus, to make kalloc_heap_zone_for_size return ZONE_NULL and enter kalloc_large, we just need to kalloc something larger than 32768 bytes.

Here is the relevant parts of kalloc_large:

__attribute__((noinline))

static struct kalloc_result

kalloc_large(

kalloc_heap_t kheap,

vm_size_t req_size,

vm_size_t size,

zalloc_flags_t flags,

vm_allocation_site_t *site)

{

int kma_flags = KMA_ATOMIC;

vm_tag_t tag;

vm_map_t alloc_map;

vm_offset_t addr;

/* ... */

size = round_page(size);

alloc_map = kalloc_map_for_size(size);

/* ... */

if (kmem_alloc_flags(alloc_map, &addr, size, tag, kma_flags) != KERN_SUCCESS) {

if (alloc_map != kernel_map) {

if (kmem_alloc_flags(kernel_map, &addr, size, tag, kma_flags) != KERN_SUCCESS) {

addr = 0;

}

} else {

addr = 0;

}

}

/* ... */

return (struct kalloc_result){ .addr = (void *)addr, .size = req_size };

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/kalloc.c

kalloc_map_for_size simply chooses the appropriate map to allocate from based on the size:

static inline vm_map_t

kalloc_map_for_size(vm_size_t size)

{

if (size < kalloc_kernmap_size) {

return kalloc_map;

}

return kernel_map;

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/kalloc.c

On my iPhone 8 and iPhone SE, kalloc_kernmap_size is 0x100001 bytes. Therefore, by kalloc‘ing something larger than 32768 bytes, we get to ignore kheap isolation and sequestering and allocate from either the kalloc map or the kernel map! What a relief… and from this point on, to simplify things a bit, I’ll be referring to the kernel map in the context of “being outside of the zone map”, even though it actually encompasses the entire virtual address space of the kernel.

kalloc_large calls kmem_alloc_flags, and kmem_alloc_flags tail calls kernel_memory_allocate. kernel_memory_allocate finds space in the vm_map passed to it by calling vm_map_find_space. The real kicker is how vm_map_find_space finds free memory:

kern_return_t

vm_map_find_space(

vm_map_t map,

vm_map_offset_t *address, /* OUT */

vm_map_size_t size,

vm_map_offset_t mask,

int flags,

vm_map_kernel_flags_t vmk_flags,

vm_tag_t tag,

vm_map_entry_t *o_entry) /* OUT */

{

vm_map_entry_t entry, new_entry, hole_entry;

vm_map_offset_t start;

vm_map_offset_t end;

/* ... */

new_entry = vm_map_entry_create(map, FALSE);

vm_map_lock(map);

if (flags & VM_MAP_FIND_LAST_FREE) {

/* ... */

} else {

if (vmk_flags.vmkf_guard_after) {

/* account for the back guard page in the size */

size += VM_MAP_PAGE_SIZE(map);

}

/*

* Look for the first possible address; if there's already

* something at this address, we have to start after it.

*/

/* ... */

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/vm/vm_map.c

“Look for the first possible address” suggests that if we make lots allocations outside of the zone map, they’ll eventually be laid out not only contiguously, but in the order we allocated them. For us, VM_MAP_FIND_LAST_FREE will not be set in flags because that’s an option specifcally for allocating new virtual memory for kheap zones.

A way to allocate predictable and contiguous memory, all while side-stepping kheaps and sequestering? Guessing a kernel pointer for an allocation outside the zone map is starting to look like it’ll work. I ended up guessing from the kernel map and not the kalloc map. Again, since the kernel map literally represents the entire kernel virtual address space, it’ll be much, much larger than the kalloc map, making it easier to guess correctly.

Now the only thing left to do is start sampling the kernel map. But what should we spray? I remember reading that OSData buffers that are larger than one page go straight to the kernel map from Siguza’s v0rtex writeup, but that’s from nearly four years ago. I checked it out myself to see if anything changed since then, and after tracking down OSData::initWithCapacity in my kernel, that is still the case:

__int64 __fastcall OSData::initWithCapacity_unsigned_int(__int64 a1, unsigned int capacity)

{

/* ... */

if ( page_size > capacity )

{

v6 = kalloc_ext(&KHEAP_DATA_BUFFERS, capacity, 0LL, &unk_FFFFFFF009260880);

/* ... */

goto LABEL_11;

}

if ( capacity < 0xFFFFC001 )

{

v8 = (capacity + 0x3FFF) & 0xFFFFC000;

/* ... */

kernel_memory_allocate(kernel_map, &v11, v8, 0LL, 0LL, v9);

}

}

So as long as our allocation is more than a page and not excessively large, we can place controlled data into the kernel map. And to make OSData allocations, we’ll take advantage of OSUnserializeBinary. This function has been around for a long, long time and there’s extensive documentation on its input data format here. IOSurfaceRootUserClient external method 9, or IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_set_value, uses OSUnserializeBinary to parse its structure input data, so we can use that to make allocations. We can also read back the data with IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_get_value or free it with IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_remove_value.

The only thing left is to actually profile the kernel map. To do this, I settled upon spraying 500 MB worth of OSData buffers for two reasons: first, it doesn’t take that long to make 500 MB worth of allocations, and second, doing that many pretty much guarentees predictable and contiguous allocations after some point. Using xnuspy, I hooked kernel_memory_allocate and checked if it was called from OSData::initWithCapacity. If it was, I recorded the address of the page it just allocated inside a global array. Since xnuspy creates shared memory out of the executable’s __TEXT and __DATA segments, the writes I did to this array were visible to my userspace code. After the spray finished, I sorted the allocations inside that array and checked if there were any holes. I ignored the first 1000 allocations because there’s a very good chance we’ll only see contiguous, in-order allocations after that point. If there were no holes, I recorded that range, and after rebooting and doing this again a couple more times, I came up with the following ranges for my iPhone 8:

[0xffffffe8cee1c000, 0xffffffe8ec458000)

[0xffffffe8cef78000, 0xffffffe8ec5b0000)

[0xffffffe8ce9b4000, 0xffffffe8ebff4000)

[0xffffffe8cef38000, 0xffffffe8ec570000)

[0xffffffe8cead4000, 0xffffffe8ec10c000)

[0xffffffe8ccdec000, 0xffffffe8ec378000)

I figured out the average of each range, added those to a list, and then took the average of that list to derive the kernel map pointer we’d guess. For my iPhone 8 running iOS 14.6, this pointer was 0xffffffe8dd594000, and has been surprisingly reliable. My iPhone SE running iOS 14.7 is another story, though. That phone’s address space is cursed. I’m not sure what causes the weirdness, but I was able to derive a guess for it nonetheless: 0xfffffff9942d0000. That guess has around a 50% success rate while my iPhone 8’s guess leans towards 90%.

You’ll find the hook for kernel_memory_allocate here, the code which analyzes the global array here, and the python script which generates the guess here.

Now that we have a guess, it’s time to start writing the exploit. I wrote the exploit in stages because stage n+1 actually running depends on the success of stage n.

Stage 0: The Goal

This “stage” is purely philosophical and serves to give context to the actual stages of the exploit.

With a pointer to use with the 32-bit increment, I started thinking about what the end goal of this exploit would be, since it wouldn’t be a fake kernel task port. How about a fake IOSurface object instead? If IOSurface::increment_use_count reads off a pointer at offset 0xc0 to increment the “use count”, I wonder if there’s an IOSurfaceRootUserClient external method to read this “use count”… oh look, there is:

kern_return_t __fastcall IOSurfaceRootUserClient::get_surface_use_count(

IOSurfaceRootUserClient *a1,

unsigned int a2,

_DWORD *a3)

{

v6 = 0xE00002C2;

lck_mtx_lock(a1->m.mutex);

if ( a2 )

{

if ( a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity > a2 )

{

v7 = a1->m.surface_client_array[a2];

if ( v7 )

{

v6 = 0;

*a3 = IOSurfaceClient::get_use_count(v7);

}

}

}

lck_mtx_unlock(a1->m.mutex);

return v6;

}

Where IOSurfaceClient::get_use_count is:

_DWORD __fastcall IOSurfaceClient::get_use_count(IOSurfaceClient *a1)

{

return IOSurface::get_use_count(a1->m.surface);

}

And IOSurface::get_use_count is:

_DWORD __fastcall IOSurface::get_use_count(IOSurface *a1)

{

return *(_DWORD *)(a1->qwordC0 + 0x14LL);

}

If we control an IOSurface object, we control the kernel pointer at offset 0xc0. Therefore, by invoking this IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_get_surface_use_count with a controlled IOSurface, we’ll have an arbitrary 32-bit kernel read. But what about an arbitrary write? This pointer at offset 0xc0 seems to have a lot of significance. I focused on it while checking out the other IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods and came across IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_set_compressed_tile_data_region_memory_used_of_plane:

kern_return_t __fastcall IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_compressed_tile_data_region_memory_used_of_plane(

IOSurfaceRootUserClient *a1,

unsigned int a2,

__int64 a3,

__int64 a4)

{

v8 = 0xE00002C2;

lck_mtx_lock(a1->m.mutex);

if ( a2 )

{

if ( a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity > a2 )

{

v9 = a1->m.surface_client_array[a2];

if ( v9 )

v8 = IOSurfaceClient::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsageOfPlane(v9, a3, a4);

}

}

lck_mtx_unlock(a1->m.mutex);

return v8;

}

Where IOSurfaceClient::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsageOfPlane is:

kern_return_t __fastcall IOSurfaceClient::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsageOfPlane(

IOSurfaceClient *a1,

unsigned int a2,

int a3)

{

return IOSurface::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsedOfPlane(a1->m.surface, a2, a3);

}

And IOSurface::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsedOfPlane is:

kern_return_t __fastcall IOSurface::setCompressedTileDataRegionMemoryUsedOfPlane(IOSurface *a1, unsigned int a2, int a3)

{

result = 0xE00002C2;

if ( a2 <= 4 && a1->dwordB0 > a2 )

{

result = 0;

*(_DWORD *)(a1->qwordC0 + 4LL * a2 + 0x98) = a3;

}

return result;

}

We control both a2 and a3, so if we control the IOSurface object passed to this function, we have an arbitrary 32-bit kernel write. But as fun as it is to think about arbitrary kernel read/write, we still haven’t figured out the steps in between.

Remember how each IOSurfaceRootUserClient keeps track of the IOSurface objects it owns? Every read from that IOSurfaceClient array is guarded behind a bounds check. If we somehow leak the address of an IOSurfaceRootUserClient we own, we can use the 32-bit increment from the type confusion to bump up its surface_client_array_capacity field. This would artificially create an out-of-bounds read past the end of its surface_client_array, so we could index into a buffer we control.

Therefore, the goal of this exploit is to construct a fake IOSurfaceClient object (which will carry a pointer to a fake IOSurface object) that we can index into using IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods. We have a long way to go until then, but each stage will bring us closer and closer.

Stage 1: Shaping the Kernel Virtual Address Space

The goal of stage 1 is to create a predictable layout of large IOSurfaceClient arrays and controlled buffers extremely close to the OSData buffer which corresponds to our guessed kernel pointer. Obviously, we need to find this OSData buffer before anything else. Just like during kernel map sampling, we’ll spray 500 MB worth of them. I chose to make allocations of 0x10000 bytes since we’ll be using that size for when we spray IOSurfaceClient arrays. This size was arbitrarily chosen and doesn’t have much meaning. However, depending on kernel map fragmentation for a given boot, the guess won’t always land on the first page of a 0x10000-byte OSData buffer. Therefore, for each page of every OSData buffer:

- Offset

0x0holds a constant value. - Offset

0x4holds the page number. - Offset

0x8holds the key used withIOSurfaceRootUserClientexternal methods 9, 10, and 11. This isn’t necessary to understand for the writeup, but it’s in my code, so I didn’t want to not acknowledge it.

After the 500 MB have been sprayed, the guessed kernel pointer is used with the 32-bit increment. If the guess landed on an unmapped page, we’ll panic, but if it landed on one of our sprayed buffers, that constant value at the start of one of those pages would have been incremented. We read back all of the OSData buffers with IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_get_value and check for this change. Once we find the page for buffer which was written to, we use the page number at offset 0x4 to calculate the address of the first page.

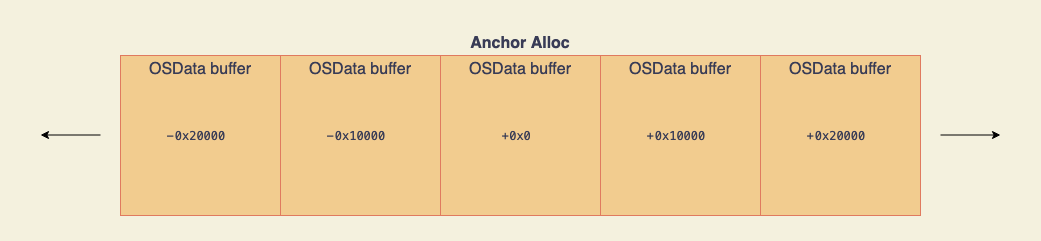

From now on, I’ll be referring to the OSData buffer which corresponds to our guessed kernel pointer as the “anchor alloc”.

We’re now in a really good position. We know the anchor alloc’s address in kernel memory, and thanks to the predictability from vm_map_find_space, these OSData buffers were extremely likely to be laid out in the order they were allocated. This is what I rely on most for this exploit. Because I know the address of the anchor alloc, I know the addresses of all the OSData buffers adjacent to it. If I want the n‘th OSData buffer to the left, then I subtract 0x10000*n bytes from the anchor alloc’s address. If I want the n‘th OSData buffer to the right, then I add 0x10000*n bytes to the anchor alloc’s address. Additionally, if we freed one of the OSData buffers, we should be able to easily reclaim that hole, due to vm_map_find_space’s “allocate the first hole we find” ideology.

I kind of spoiled the fact that we can create IOSurfaceClient arrays in the kernel map by saying that we’re making each of them 0x10000 bytes. If you’ve reversed the IOSurface kext before, or have looked at the kernel log, you may know that there is a limit of 4096 IOSurface objects per IOSurfaceRootUserClient. That isn’t an issue, though. Once we hit that limit for one IOSurfaceRootUserClient, we can just create another and continue making IOSurface objects with the new one. Again, for every IOSurface object we create, there will be an IOSurfaceClient object. But even if we create 4096 IOSurface objects, sizeof(IOSurfaceClient *) * 4096 is only 0x8000 bytes, not 0x10000 bytes. So what gives?

The answer boils down to IOSurfaceRootUserClient::alloc_handles:

__int64 IOSurfaceRootUserClient::alloc_handles(IOSurfaceRootUserClient *a1)

{

surface_client_array_capacity = a1->m.provider->m.surface_client_array_capacity;

surface_client_array = a1->m.surface_client_array;

/* ... */

v5 = IONewZero(8 * surface_client_array_capacity);

a1->m.surface_client_array = v5;

if ( v5 )

{

a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity = surface_client_array_capacity;

/* ... */

}

/* ... */

}

You may remember seeing a call to this function inside IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle, which I showed earlier in this writeup. IOSurfaceRootUserClient::set_surface_handle is called from IOSurfaceClient::init, so we reach IOSurfaceRootUserClient::alloc_handles every time we create a new IOSurface object.

It’s this line that makes the 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient array possible:

surface_client_array_capacity = a1->m.provider->m.surface_client_array_capacity;

The provider field points to an IOSurfaceRoot object. From what I can tell, every IOSurfaceRootUserClient object I create has the same provider pointer. So how does IOSurfaceRoot come into play when creating a new IOSurface? One of the very first functions to be called when you create an IOSurface is IOSurface::init. To allocate a new IOSurface ID, it calls IOSurfaceRoot::alloc_surfaceid:

__int64 __fastcall IOSurfaceRoot::alloc_surfaceid(IOSurfaceRoot *a1, unsigned int *new_surface_idp)

{

/* ... */

v4 = a1->m.total_surfaces_created >> 5;

while ( v4 >= a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity >> 5 )

{

LABEL_7:

if ( (IOSurfaceRoot::alloc_handles(a1) & 1) == 0 )

{

v9 = 0LL;

goto LABEL_15;

}

}

/* ... */

v6 = 32 * v4; /* aka v6 = v4 << 5 */

a1->m.total_surfaces_created = v6 + 1;

*new_surface_idp = v6;

/* ... */

}

Why this codebase stores the total number of IOSurface objects created shifted to the left five bits is beyond me, but we see that IOSurfaceRoot has its own alloc_handles implementation:

__int64 __fastcall IOSurfaceRoot::alloc_handles(IOSurfaceRoot *a1)

{

surface_client_array_capacity = a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity;

if ( surface_client_array_capacity )

{

if ( surface_client_array_capacity >> 14 )

return 0LL;

v3 = 2 * surface_client_array_capacity;

}

else

{

v3 = 512;

}

/* ... */

v6 = IONewZero((v3 >> 3) + 8LL * v3);

if ( v6 )

{

a1->m.surface_client_array_capacity = v3;

/* ... */

}

/* ... */

}

So there’s a system-wide limit of 16384 IOSurface objects, which is what surface_client_array_capacity >> 14 tests for. For every power of two above 512, the IOSurfaceRoot’s surface_client_array_capacity will be doubled. And because every IOSurfaceRootUserClient we create has the same IOSurfaceRoot pointer, they all see the same surface_client_array_capacity field in IOSurfaceRootUserClient::alloc_handles.

Thus, the way we create 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient arrays is simple: create two IOSurfaceRootUserClient objects and allocate 4096 IOSurface objects with each of them. If we take special care to not trigger another doubling of their provider IOSurfaceRoot’s surface_client_array_capacity, all future IOSurfaceClient arrays for any new IOSurfaceRootUserClient object will also be 0x10000 bytes. The awesome thing here is all we need to do to make a new 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient array with a new IOSurfaceRootUserClient object is to allocate just one IOSurface with it, because at that point, the IOSurfaceRoot’s surface_client_array_capacity will already be 8192.

Alright, so the mystery of the 0x10000-byte kernel map IOSurfaceClient array is solved. Even though 0x10000 is larger than kalloc_max_prerounded, there’s a small issue: while OSData buffers are allocated directly by kernel_memory_allocate, the IOSurfaceClient array allocation goes through kalloc_ext, so kalloc_large will be called. Remember how kalloc_large calls kalloc_map_for_size? Here it is if you forgot:

static inline vm_map_t

kalloc_map_for_size(vm_size_t size)

{

if (size < kalloc_kernmap_size) {

return kalloc_map;

}

return kernel_map;

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/kalloc.c

kalloc_kernmap_size is again 0x100001 bytes, but we are making IOSurfaceClient arrays that are only 0x10000 bytes, so we’ll be allocating from the kalloc map instead of directly from the kernel map. Here’s the relevant part from kalloc_large:

alloc_map = kalloc_map_for_size(size);

/* ... */

if (kmem_alloc_flags(alloc_map, &addr, size, tag, kma_flags) != KERN_SUCCESS) {

if (alloc_map != kernel_map) {

if (kmem_alloc_flags(kernel_map, &addr, size, tag, kma_flags) != KERN_SUCCESS) {

addr = 0;

}

} else {

addr = 0;

}

}

xnu-7195.121.3/osfmk/kern/kalloc.c

Oh, so we just have to make the allocation from the kalloc map fail to fall into the second kmem_alloc_flags, which will always allocate from the kernel map. The best way to make future kalloc map allocations fail is to fill it up completely.

To fill up the kalloc map, we’ll use Mach messages that carry out-of-line ports. This was one of the most over-powered strategies on iOS 13 and below because you could get an array of Mach port pointers placed into any zone you wanted. Even though that’s dead on iOS 14 and above, the port pointer array allocation still goes through kalloc_ext. After some testing, spraying 2000 messages carrying 8192 send rights consistently fills up the kalloc map, since an ipc_port pointer is created for every send right in the message.

Now that the kalloc map is filled, every kalloc allocation of more than 32768 bytes goes right into the kernel map. The last piece to this puzzle is to figure what kind of controlled buffer we want to use. I mean, I could have continued to use OSData buffers, but a ton of code is required to read from, write to, or free them, unlike a pipe buffer…

static const unsigned int pipesize_blocks[] = {512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 4096 * 2, PIPE_SIZE, PIPE_SIZE * 4 };

/*

* finds the right size from possible sizes in pipesize_blocks

* returns the size which matches max(current,expected)

*/

static int

choose_pipespace(unsigned long current, unsigned long expected)

{

int i = sizeof(pipesize_blocks) / sizeof(unsigned int) - 1;

unsigned long target;

/*

* assert that we always get an atomic transaction sized pipe buffer,

* even if the system pipe buffer high-water mark has been crossed.

*/

assert(PIPE_BUF == pipesize_blocks[0]);

if (expected > current) {

target = expected;

} else {

target = current;

}

while (i > 0 && pipesize_blocks[i - 1] > target) {

i = i - 1;

}

return pipesize_blocks[i];

}

xnu-7195.121.3/bsd/kern/sys_pipe.c

When you create a pipe using the pipe system call, memory for the backing pipe buffer is not allocated until you write to it. The size of the first write is the first thing that determines how large of an allocation the pipe buffer will be. This is exactly what choose_pipespace is for, and pipesize_blocks lists the possible allocation sizes. But what is PIPE_SIZE?

/*

* Pipe buffer size, keep moderate in value, pipes take kva space.

*/

#ifndef PIPE_SIZE

#define PIPE_SIZE 16384

#endif

The last int in pipesize_blocks is 16384 * 4, or 0x10000. Therefore, all we need to do to allocate a pipe buffer straight from the kernel map is to write 0x10000 bytes to it.

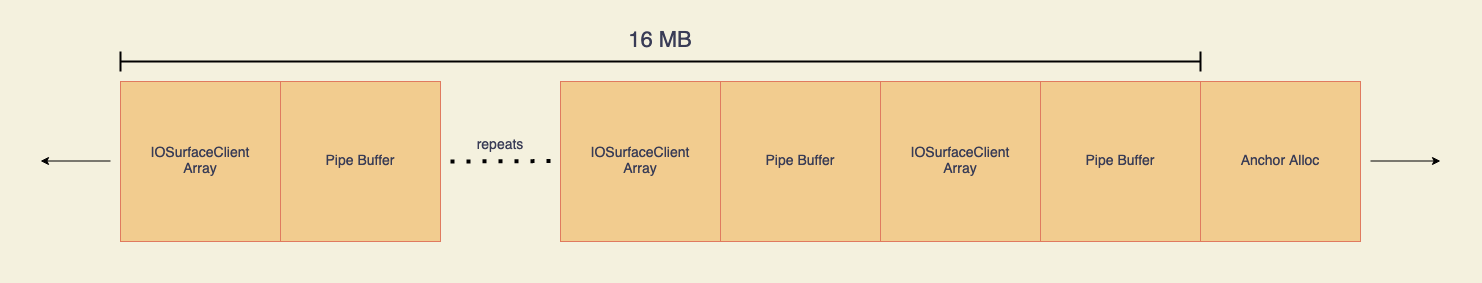

Thus, the goal, or the “predictable layout” mentioned at the beginning of this stage, will simply be side-by-side 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient arrays and pipe buffers. Once we bump up surface_client_array_capacity in some IOSurfaceRootUserClient object we own, whatever pipe buffer is directly after the IOSurfaceClient array that capacity corresponds to is the controlled buffer that we’ll be reading into out-of-bounds.

To get 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient arrays and pipe buffers side by side, all we have to do is free a good amount of space, and then alternate between allocating 0x10000-byte IOSurfaceClient arrays and pipe buffers. For the “good amount of space”, I chose to use the 16 MB to the left of the anchor alloc. Why 16 MB to the left? That’s honestly lost to time, I just remember experimenting a ton and that’s what had the best reliability.

At the end of stage 1, the 16 MB to the left of the anchor alloc will look like this:

Stage 2: The Best (Artificial) Info Leak Ever

Let’s travel back in time to iOS 13.1.2 for a second. zone_require was botched, there were no kheaps or sequestering, and tfp0 was still a thing. Because tfp0 was still a viable end goal while I was exploiting the kqworkloop UAF, I used the 32-bit increment primitive I got from reallocating the UAF’ed kqworkloop object to partially overlap two adjacent Mach ports. I used mach_port_peek on the partially-overlapped port to leak ikmq_base of the port it overlapped with, as well as the address of the overlapped port itself. The only difference this time around is that we’re dealing with IOSurfaceClient objects and not Mach ports…

I spent some more time reversing the IOSurfaceClient structure. In addition to carrying a pointer to the IOSurface object it manages at offset 0x40, it also carries a pointer to the IOSurfaceRootUserClient object that owns that surface at offset 0x10. We’ll add this field to IOSurfaceClient in the IOSurface relationship diagram that was shown earlier:

This got me thinking, because most IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods follow this pattern:

- Read the

IOSurfaceClientarray from theIOSurfaceRootUserClient. - Index into that array with the

IOSurfaceID from userspace for anIOSurfaceClientobject. - Pass the

IOSurfacepointer from thatIOSurfaceClientto a function that does the work for that external method.

What if the surface pointer from step 3 pointed to an IOSurfaceRootUserClient instead? Would the external methods that are meant to return fields from that surface inadvertently leak valuable fields from that user client?

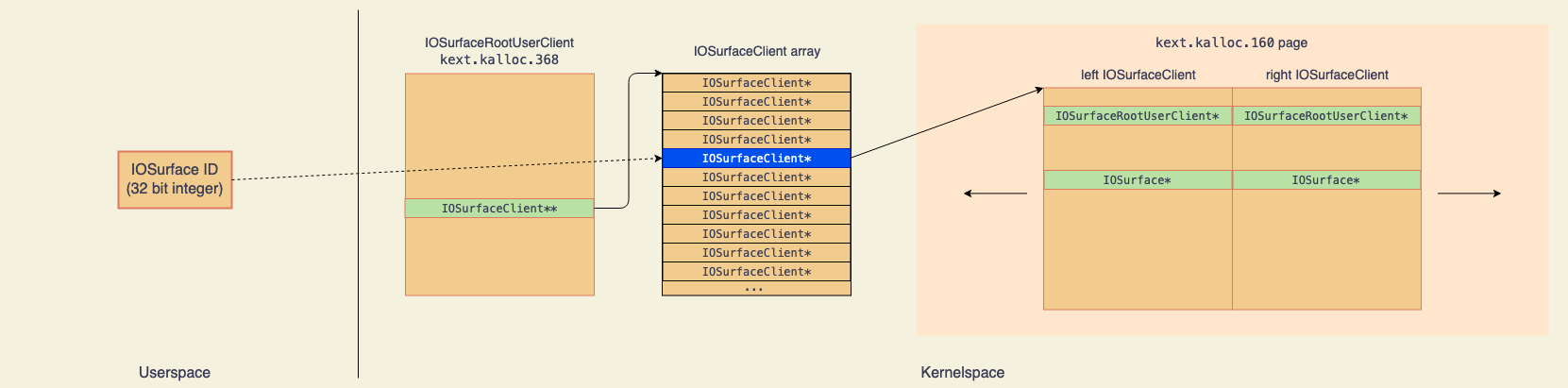

Stage 1 actually does a bit more work after it shapes the kernel’s address space: it’ll spray a ton of IOSurfaceClient objects to create a bunch of pages with just those objects. That way, for an arbitrary IOSurface ID, the chance of its corresponding IOSurfaceClient being adjacent to other IOSurfaceClient objects is extremely likely. And from now on, I’ll be referring to two adjacent IOSurfaceClient objects as a “pair”, where one is on the left side and the other is on the right side.

Now we just apply the overlap strategy I used in iOS 13.1.2 to one of those pairs. Since I don’t have any way of knowing if a surface ID will correspond to the left side of a pair, I’ll make an educated guess. If guessed right, I’ll have something like this, where the blue IOSurfaceClient pointer in the array points to the one on the left:

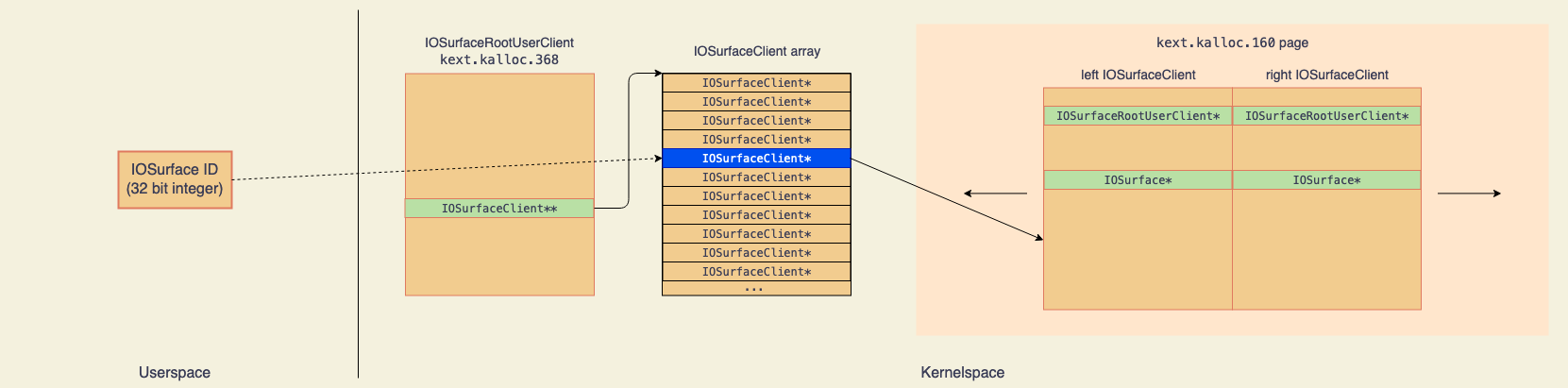

The idea is to have the kernel read off the end of the left IOSurfaceClient and onto the right IOSurfaceClient when it goes to read the left’s IOSurface field. Since we can derive the address of the surface client array because it’s extremely close to the anchor alloc, we’ll achieve this by incrementing the left’s pointer in that array. To recap:

offsetof(IOSurfaceClient, IOSurface)is0x40offsetof(IOSurfaceClient, IOSurfaceRootUserClient)is0x10- each

IOSurfaceClientobject takes up0xa0bytes, since they live inkext.kalloc.160

The distance from the left’s surface field to the end of the kext.kalloc.160 element it lives on is 0xa0 - 0x40, or 0x60 bytes. But this only overlaps the left’s IOSurface field just enough to read the right’s vtable pointer at offset 0x0, so we need an extra 0x10 bytes to read the right’s IOSurfaceRootUserClient field instead. Therefore, we’ll increment the left’s pointer 0x70 bytes with the 32-bit increment primitive. Afterward, it will point a bit more than halfway into the left:

If our guessed surface ID was wrong, then we’ll panic shortly after this point, but if it was correct, we can now read bytes from an owned IOSurfaceRootUserClient by using the surface ID which corresponds to the left. I had a lot of fun seeing what I could leak by treating IOSurfaceRootUserClient external methods as black boxes, but nothing could have prepared me for what I saw in the 0x80 bytes of structure output after invoking IOSurfaceRootUserClient external method 28, or IOSurfaceRootUserClient::s_get_bulk_attachments. Here’s a dump of that structure output I had laying around:

0x16eea33f8: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

0x16eea3408: 00 00 00 00 AO 5C A2 CB E4 FF FF FF 00 F8 10 CC

0x16eea3418: E4 FF FF FF 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 80 B2 7F 9A

0x16eea3428: E1 FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 28 FB 13 CB

0x16eea3438: E4 FF FF FF E0 A4 A4 CC E4 FF FF FF F8 A4 A4 CC

0x16eea3448: E4 FF FF FF 00 40 3A E7 E8 FF FF FF 00 20 00 00

0x16eea3458: 00 00 00 00 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

0x16eea3468: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

That buffer includes many kernel pointers, but the ones we’re interested are pointers to…

- an

IOSurfaceRootobject, at offset0x1c. - an

IOSurfaceRootUserClientobject we own, at offset0x3c. - the

IOSurfaceClientarray belonging to theIOSurfaceRootUserClient, at offset0x54.- the capacity of that array (divided by

sizeof(IOSurfaceClient *)) is also at offset0x5c.

- the capacity of that array (divided by

The only catch is that the IOSurfaceRootUserClient pointer is shifted 0xf8 bytes, but that’s as simple as subtracting 0xf8 from it to derive the original pointer. I literally could not have asked for anything better than this.

Stage 3: One Simple Trick iOS 14.7 Hates

We enter stage 3 with the pointers to our owned IOSurfaceRootUserClient object and its IOSurfaceClient array. But this isn’t just any IOSurfaceClient array—it’s one we sprayed all the way back in stage 1, so there will be a pipe buffer right next to it. We aren’t sure which pipe buffer is right next to it, though, but we can derive its address by adding 0x10000 to the leaked IOSurfaceClient array pointer. The first thing we do in stage 3 is set up all the pipe buffers we sprayed in stage 1 in the following manner:

- Offset

0x0contains the derived pipe buffer address, plus eight. - Offset

0x8contains a fakeIOSurfaceClientobject. - Offset

0xa8contains a fakeIOSurfaceobject.- Offset

0xc0of the fakeIOSurfacepoints to somewhere in the pipe buffer where I wrote its index in the array that contains all the sprayed pipes from stage 1. I do this so I can figure out which pipe buffer houses our fake objects later.

- Offset

Now that all the pipe buffers are set up, I use the 32-bit increment to bump up the capacity for the leaked IOSurfaceRootUserClient object by one.

To figure out which owned IOSurfaceRootUserClient was corrupted, I loop through all of them and see if I get something other than an error when I invoke IOSurfaceRootUserClient::get_surface_use_count with a surface ID that indexes into the start of the adjacent pipe buffer. If there was no error, I found the corrupted one, and the four bytes of scalar output is the index of the pipe which holds the fake IOSurfaceClient and IOSurface objects.

Now that we have control over an IOSurface object, we can set up arbitrary kernel read/write APIs with the external methods talked about in stage 0. And with that, the phone is pwned, and we can start to jailbreak it. Although, I’ll leave that to those who want to undertake it because my exploit requires a guessed kernel pointer. It’s not plug-and-play and more of a research project.

The exploit code is here. It should work on A12+ because I didn’t attack any PAC’ed data structures.

If you have any questions, I’d prefer it if you’d contact me on Discord (Justin#6010), since Twitter likes to not notify me about DMs.